Goodwill Book Review*: Hopper

A book of paintings of our isolation by Edward Hopper, one of America's great 20th Century artists

Early in his artist life, Edward Hopper (1882-1967) went to Paris, which was where young artists of the time aspired to live. Impressionism and modern art were in vogue. Picasso, Matisse, and others.

I was struck reading this book that Hopper visited Europe as a young artist three times, but, uninterested or unimpressed by the avant-garde, he returned to the United States in 1910 and never went back.

Instead, he lived, married, and painted in New York City and Massachusetts and devoted himself to themes of America and unadorned realism.

The strange thing is, he did so by removing most Americans.

Reading through this beautiful book that I found at my Goodwill Outlet, I was struck by the fact that his country seems almost absent of people.

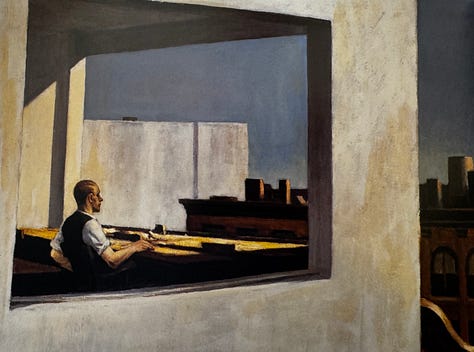

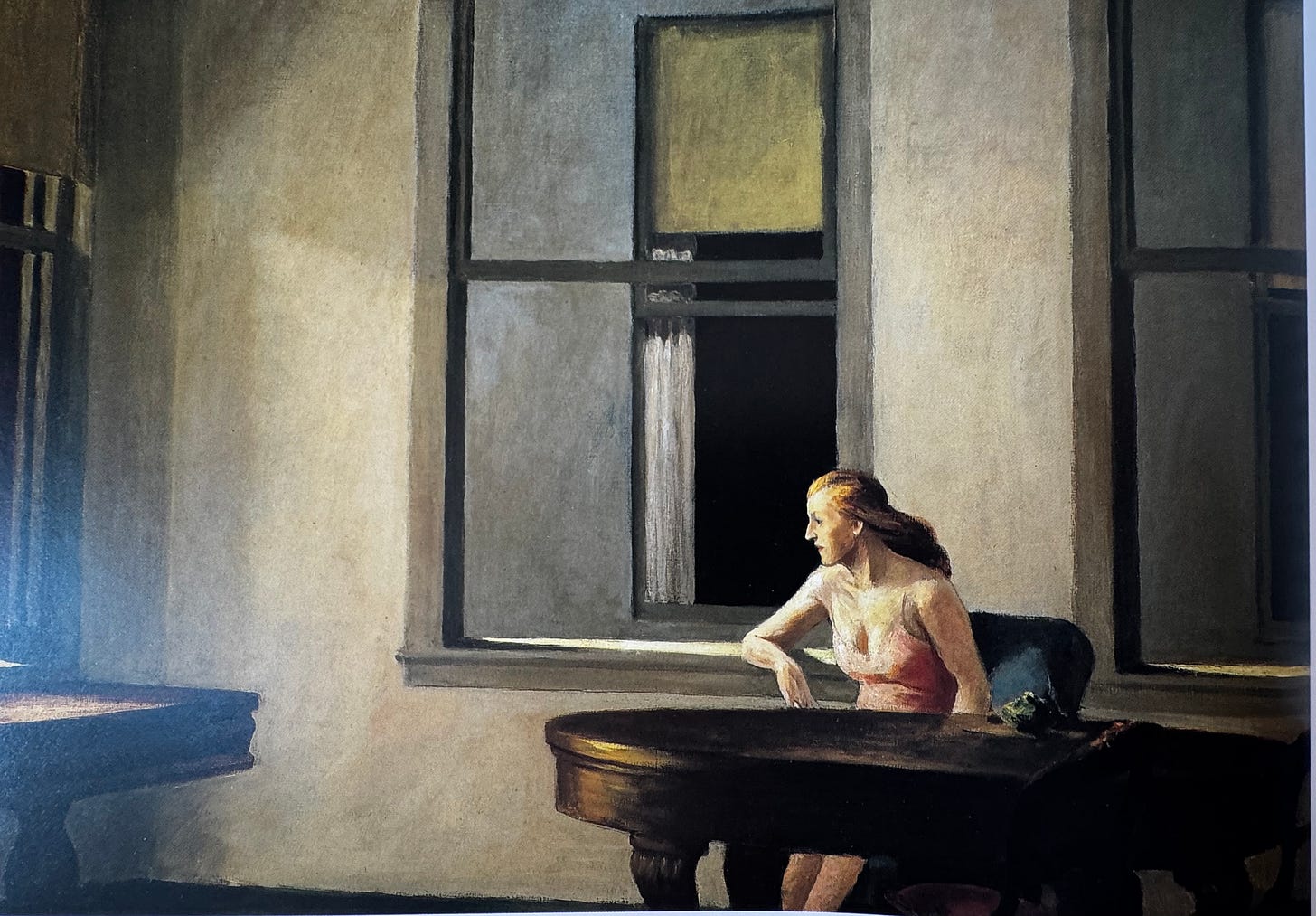

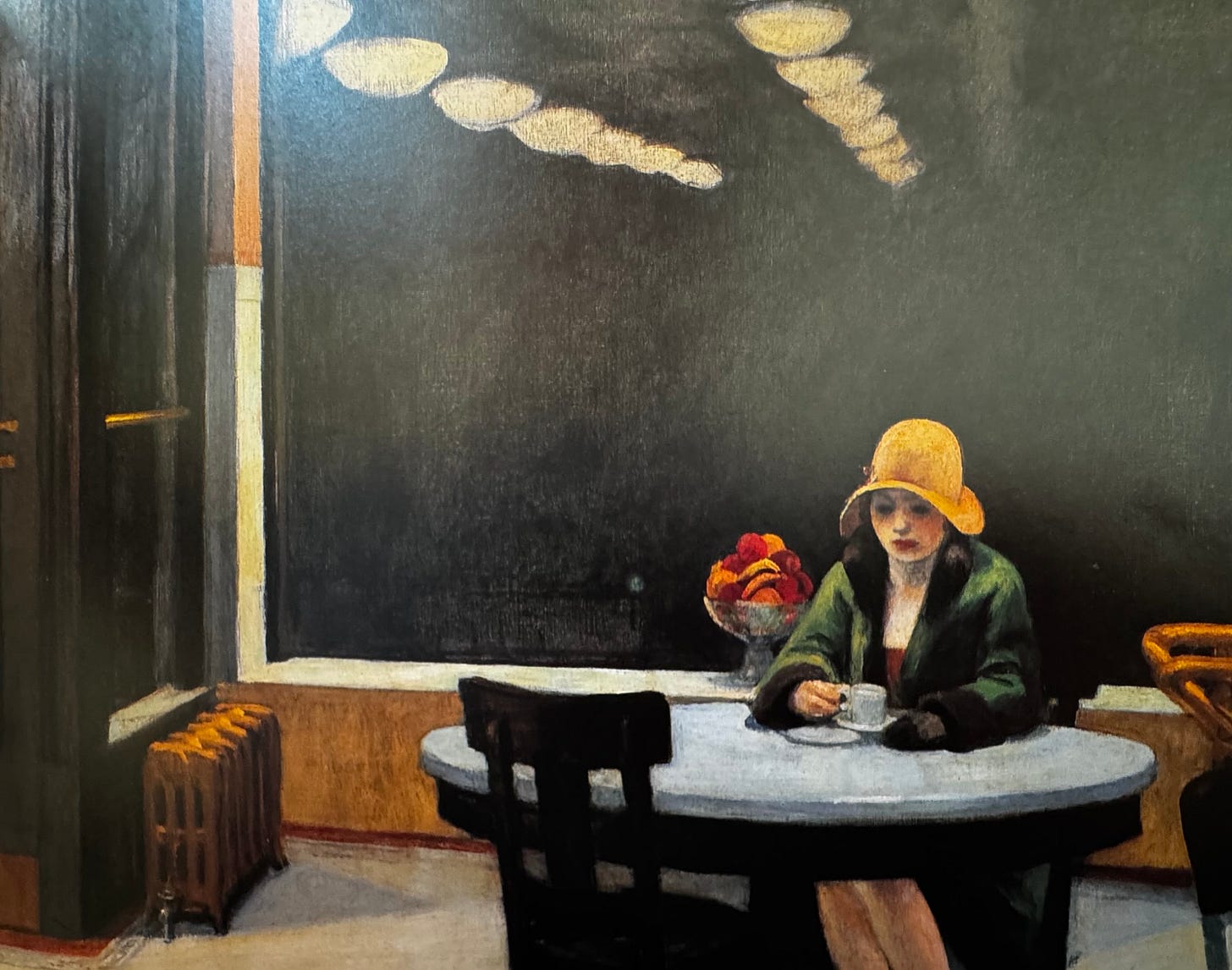

He paints theaters, city sidewalk, cafes and restaurants, yet they are almost always empty, occupied by a lone subject usually with a far-off stare suggesting the scene before her is as empty as the room she inhabits. His city streets have no people, no cars, no street vendors

His art reminds me of scientists who try to isolate for variables in an experiment, eliminating all the extraneous so-called noise, to get to the clearest expression of truth.

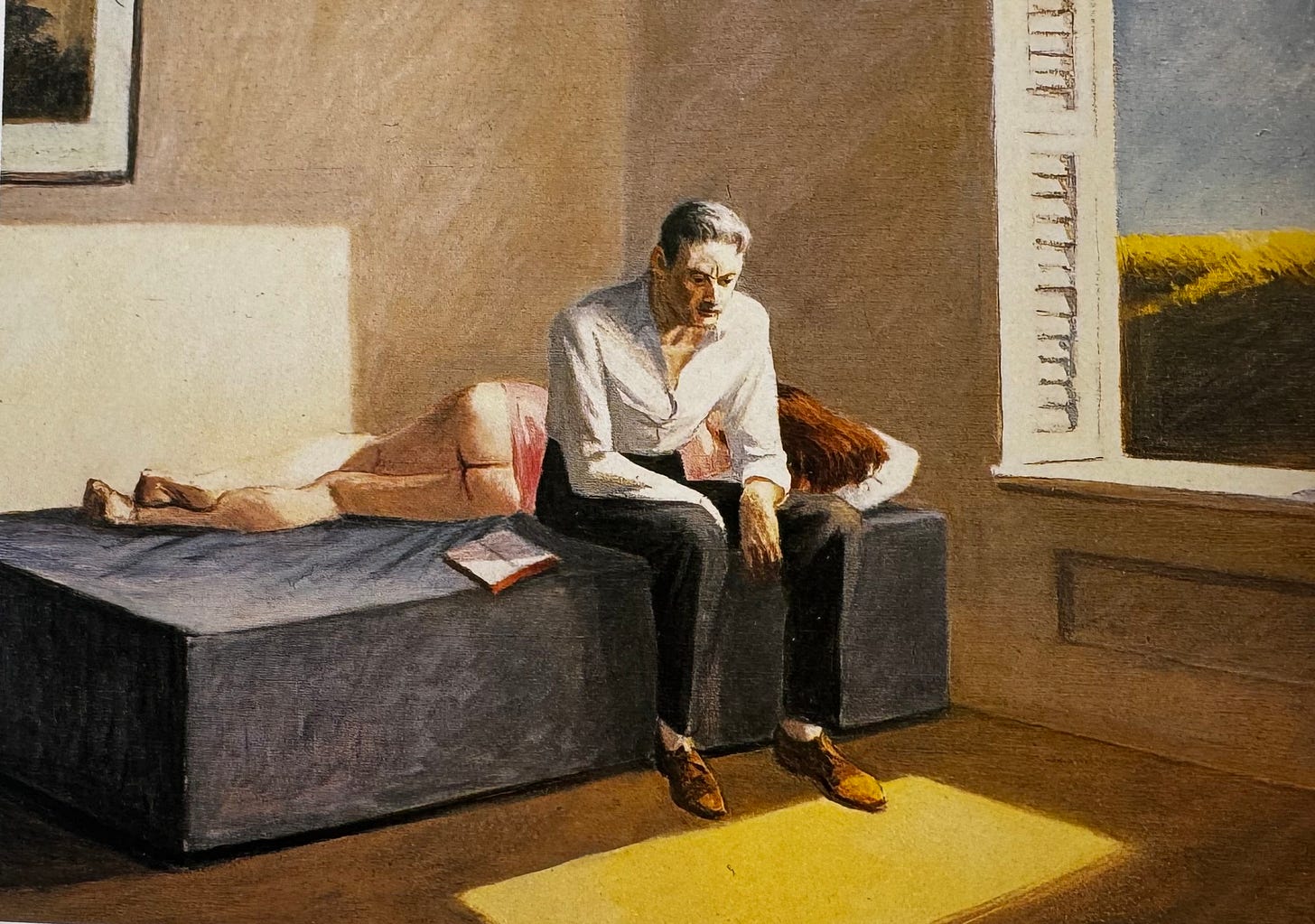

Those Americans who remain in Hopper’s paintings seem disappointed, missing out on something that makes life worth living. We see them alone with their thoughts that we’re free to imagine, but which we can’t believe are joyful. Certainly, no one’s laughing.

Perhaps Hopper appeals to me because he leaves social criticism out of his art. I prefer artists who do that. He lets details tell what story viewers would gather for themselves from each painting.

This is remarkable because in his day social criticism was viewed as what a politically aware artist should produce.

I’m a journalist. I believe facts and details, accumulated into stories, without many adjectives or adverbs, is the most powerful kind of nonfiction writing. You’re more likely to impact a reader that way. You just can’t control what that impact will be. You have to be fine with that.

Think of the difference between Bob Dylan and the folksingers he broke with shortly into his career. They wanted him to sing protest songs, the message of which was always clear. He wanted to write uncorseted.

Hopper’s painting left out the adjectives, the adverbs, figuring, I guess, that we could all interpret his art the way it occurred to each of us. Which in the end is the most radical idea — that we can each have our own version of art, of truth. That also may be why he rarely did interviews.

My copy of Hopper I found buried deep in a Goodwill Outlet bin beneath the sedimentary layers of self-help books, both secular and Christian.

But leafing through pages of Hopper’s paintings, I was struck by what his works have in common with those tomes.

Those books are artifacts of the search we all undertake in one form or another for some kind of place in the world. It’s a place we feel passing us by at times in our lives when we feel we should see the path forward more clearly, have things more resolved.

The figures in Hopper’s paintings seem filled with a similar longing. They never face us. They’re reluctant to look us in the eye. They’re always alone, lost in (often anguished) thought or engrossed by something out on the street that they observe from a sad apartment, or an empty café or office.

His paintings “reveal a human world that is no longer in a state of innocence, but has not yet reached the point of self-destruction,” writes Ivo Kranzfelder, author of analysis of his career included in this book.

It's as if Hopper was documenting the beginnings of an American isolation that deepened and came into sharpest relief decades later with our opioid-addiction epidemic.

Our economy has a way of turning so many activities into alienating, solitary pursuits that lead to compulsion. A company has no better customer than one who is addicted to its product. Shopping, gambling, which once had to be done in public, now can be done on apps, alone. Porn does the same with sex.

Today that isolation is everywhere, intensely damaging, and giving rise to the worst symptoms of depression, mental illness, addiction, and suicide.

I spoke recently with an official of a midwestern city medical examiner’s office who said that fentanyl was falling in supply since late 2023 and opioid overdoses were dropping, but that suicide was rising. “Gunshots, hangings, purposeful overdose – from kids to seniors,” the official said. Kids “don’t know how to cope, don’t know how to fail. Meth may be causing mental health issues, too.”

What would Edward Hopper make of our world of Airpods, smart phones, remote work, and whatever AI is about to bring – a world he may scarcely have been able to imagine?

Like the people in his paintings, we are as isolated in our public places as we are in our homes. I go to a gym and people rarely talk. The sounds are all metallic, machine generated. Like a factory. I write at independent cafes. They’re usually fairly quiet. I’m as much to blame. I put on my earphones and listen to music as I write. Don’t often engage in conversation, though I wish I would.

The places I know where people used to flock – Fisherman’s Wharf and downtown San Francisco and Venice Beach in Los Angeles are recently on my mind – are about as barren as Hopper’s theaters and cafes.

One difference is that the people in those places I’ve visited recently are too often captured and alone with the most tormented mental illness and addiction. Perhaps Hopper’s half-dressed woman alone in her room is no longer the reflection of our country that he imagined. Maybe, instead, it’s a homeless woman, looking out from under her street tent, her face contorted in anguish at a merciless hallucination conjured by some methamphetamine so cheap that she got it for free.

Or maybe that’s just me, like Hopper, too long taken up with one aspect of the country.

I’ve long thought that one reason meth addiction gets so little sympathy is because it reveals something deep and true about us that we’re forced to turn from it in, what?, disgust? Anguish?

It’s interesting that Hopper once said he was never able to depict exactly what he intended. I feel him. I always have a mental idea of how a story can go that is different from what I’m later able to come up with.

But that’s the most optimistic idea in Hopper’s work. Each time, he must have known that the painting he conceived would not turn out just as he had it in his mind’s eye. He did it anyway.

I think that’s the best we can do, despite feelings we haven’t figured life out the way we should have by now: Just imagine what might be possible, then take a stab at it.

Then repeat, getting closer through the practice, though never quite there.

*Here’s a video introduction to my Goodwill Book Reviews — just fyi.

Thank you for sharing your Goodwill treasure! Hopper's "Nighthawks" is at the Art Institute of Chicago, where I was an art history grad student. I would go in to look at the Chinese bronzes (because I was supposed to be studying those) and end up with Nighthawks and George Inness's moody landscapes. It seems that each of these Hoppers could be the basis for a novel or a short story. I love the gas station painting. I did some poking around and there are several gas station paintings. I found that this one is called "Four Lane Highway." It reminded me immediately of the hardboiled noir novel, "The Postman Always Rings Twice" by James W. Cain.

Thank you Sam The Man,

You report an insightful therapeutic activity. You remind me that’s an activity I used to partake in. Lately, I visit our local small “goody bookstore” where old library books are sold for pennie’s.

One thing I wanted to mention is how lonely writing can be. Your activity is a reflection of that, but going to the goodwill takes you to where you’re surrounded by people. Congrats on finding a great habit!