Mennonites, Drug Trafficking, and Measles

My encounter years ago with Mexico's Narco-Mennonites and what that has to do with a measles outbreak and a child's death in Texas today.

The nation’s first measles death in a decade took the life of a Mennonite child from Gaines County, Texas.

The Gaines County seat is the town of Seminole, which, it’s relevant to note, is a center in the U.S. of Old-Colony German Mennonites from Mexico, who migrated north in the last decades.

That news reminded of me of the scariest moment of my 10 years as a freelance reporter living in Mexico. One I could hardly forget.

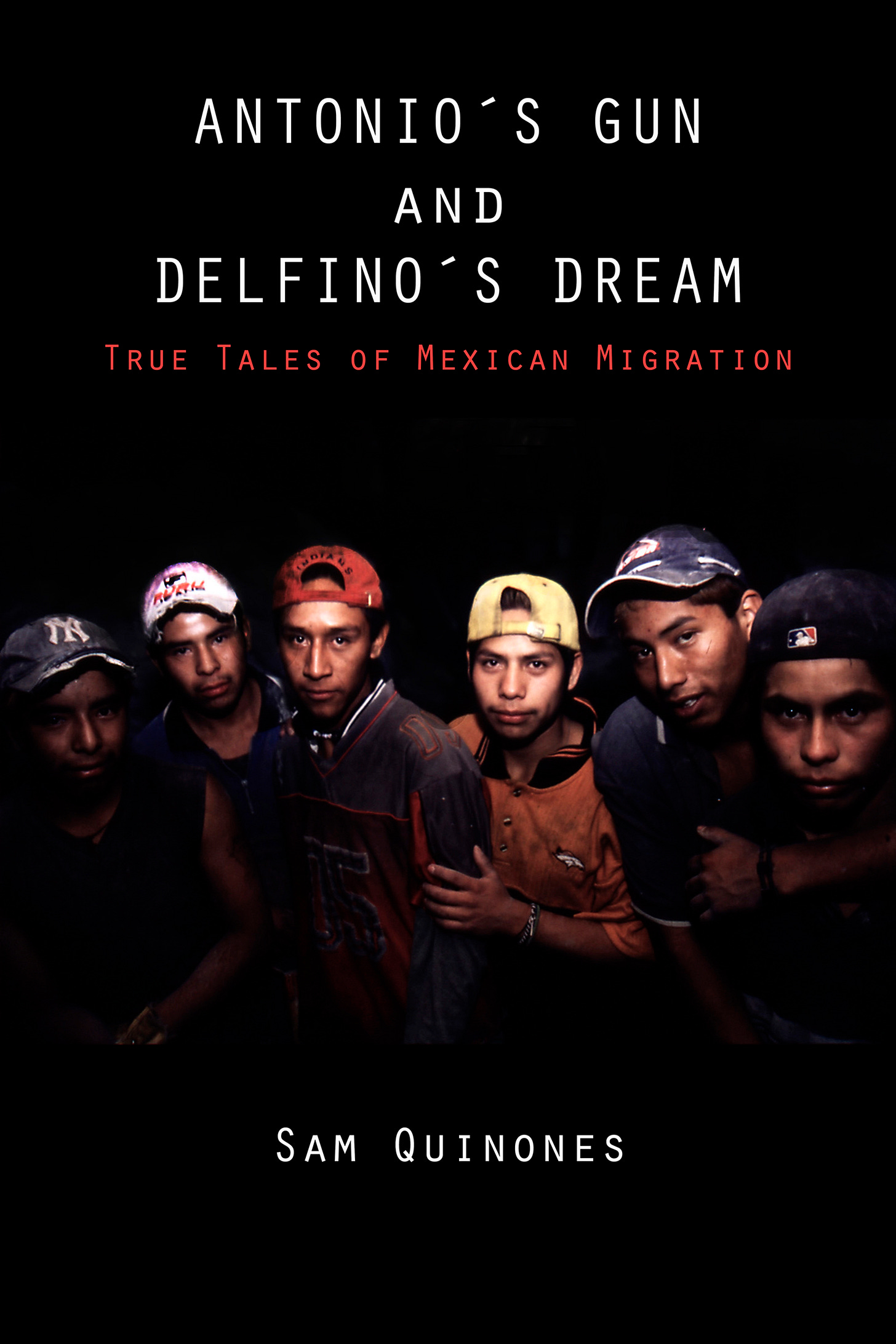

It was a 2004 encounter with drug-traffickers from those Mennonite communities in northern Mexico. I tell this tale in the last chapter of Antonio’s Gun and Delfino’s Dream: True Tales of Mexican Migration.

I went twice to the Mexican Mennonite colonies — near the town of Cuauhtemoc, four hours south of Juarez — because I wanted to write about the most surprising story I’d heard in a long time:

That a sizable number of seemingly pious, religious Old World German Mennonite farmers, in overalls and straw hats and making nationally known cheese, were, in fact, traffickers aligned with the Juarez Drug Cartel. (Post continued below …)

The second trip ended with a terrifying race out of there as I was followed by a tag-team of mobbed-up, blond-haired, blue-eyed Germanic men who less than two decades before were in horse and buggy but now were driving Dodge Stratuses and gleaming Chevy pickups, all unlicensed, in an episode which, as I said, you can read all about in the book above. ($4.99 on Kindle)

So what does this have to do with measles and unvaccinated kids (18 percent of Seminole’s schoolchildren are reportedly unvaccinated)?

The motivations to traffic drugs of the guys who followed me are the same that keep people from getting vaccinated, said one Mennonite man, to whom I have turned often through the years to understand his community. He grew up in the Mexican Mennonite colonies, then moved to Canada.

“We’re hard-working but we have this attitude that is — nobody can tell me what to do,” he told me. There’s also a culture of flouting prohibitions that has grown deep in Old Colony Mennonite farming communities in northern Mexico, Seminole and elsewhere, he said.

These attitudes are behind why some Mennonites have, since the 1970s emerged as proficient drug traffickers, and, more recently, why many Mennonite churches rebelled against Covid vaccines, incited, he said, by anti-vax misinformation.

All this is connected, he said, to an important motivator for Old Colony Mennonites: the conviction they are God’s chosen people, separate from others, destined for heaven due to their separateness, and that obeying the laws of one government after another is not always necessary. After all, since the sect’s formation in 1525, Mennonites have been run out of: Switzerland, Poland, Germany, Russia, Canada.

The old-world version of the sect moved to Mexico from Canada in the 1920s and has since expanded mightily. Many in that community are talented dairy farmers, mechanics and other tradespeople and have nothing to do with drug trafficking.

However, Mexican Mennonite drug trafficking also took hold in these communities, beginning in the 1970s. On the lure of quick money, it, too, expanded mightily. That money helped some hold onto their farms, and was rationalized by Mennonite distrust of governments.

By then, too, Old-Colony Mennonites were rebelling against the prohibitions of even their own pastors — prohibitions that had become part of the sect’s tenets over generations: against rubber-tired tractors, radios, sports, and music. In this culture of pervasive flouting of such edicts, drug trafficking took hold. It was aided by passports that allowed Mennonites in northern Mexico to travel through the United States on their way between Mexico and Canada.

Some families grew powerful on drug money. The Harms family was one. The patriarch, Abraham Harms, was the first Mennonite kingpin arrested for trafficking marijuana to Canada. Released on bail, he fled to Mexico, where he was killed in mid-1980s auto crash. His sons, principally Enrique Harms (indicted in Oklahoma), emerged as kingpins, allying with the Juarez Cartel.

Abraham Harms has a musical and a corrido, a Mexican ballad, “El Corrido de Abraham” — written about him and his death. (Again, read the last chapter in my second book for more on this.)

Seminole, with its large Old Colony Mennonite population that emerged in the 1970s, became also a drug distribution hub, as Mennonite trafficking expanded.

More recently, Covid overlaid a layer of fear and fueled resistance to government edicts. The issue of vaccinations has riven the community, dividing families, he said. “Many people still believe Bill Gates is trying to infect them. Churches refused to close (during Covid). One was fined $400,000.”

Let me say that Mennonites of many kinds have become valued, admired members of their communities into which they have assimilated.

Generally, though, Old-Colony Mennonites still live in a kind of benighted, self-imposed underdevelopment, created by dim education that in 2004, I thought, resembled something out of the 19th-Century. I visited a one-room schoolhouse where kids’ education amounted to writing Biblical scripture in chalk on slates. The teacher, a farmer, asked me to confirm if 6x7 equaled 42.

All this means, my source said, that many Old Colony Mennonites — in Mexico and in Seminole — are unprepared for the modern world they will meet, and often unable to find decent-paying work, vulnerable to both misinformation and the lure of easy drug money.

“Mennonites who did not come from the Old Colony are mostly educated, career-minded,” he said. “You don’t see the drug-dealing problems or the anti-vax (sentiment). That mainly comes in the old-order Mennonites.”

Sam this is POWERFUL and of course I’m going to buy it.As always Thanks.